Art Education beyond Anthropocentrism - Beatrice Portelli

Beatrice Portelli

In my research, I explore how contemporary artistic practices can deepen our understanding of human and non-human relationships in art education. I seek to bridge my own interests as an artist and art educator with broader discussions around anthropocentrism by examining how art educators can empower students to foster a sense of responsibility and compassion toward other species in a world where subjection of other species is an everyday norm. In order to do this, I explore art educators’ perceptions and their pedagogical approach towards the topic, including the challenges, successes and aspirations for the future. I also explore the ideas of Education forSustainable Development (ESD) educators to see how anthropocentrism is currently addressed within their field, identify effective strategies for integrating concepts of sustainability into the curriculum and to obtain feedback on potential improvements or gaps in existing educational approaches. In my research, the data obtained informed the formulation of ten lesson plans, aimed at guiding teachers to look beyond anthropocentrism, fostering critical thinking skills and a holistic understanding of humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

Anthropocentrism, deeply rooted in Western philosophy through figures like Aristotle, Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Descartes and Kant has long shaped societal attitudes. I propose a shift away from anthropocentric perspectives to embrace a post-human ideology through contemporary art; a tool to challenge traditional ideas, offering alternative viewpoints that reveal much about current power structures and ideologies. While classical humanism has often emphasised a division between humans and non-human animals, depicting them as viewing each other across “an abyss of non-comprehension” (Berger, 2009), art educators can help bridge this gap. Thus, by promoting a “non-hierarchical gaze” educators can move beyond economic views of non-human animals and rethink this binary distinction (Vella, 2023, p. 36).

I outline several pedagogical implications that art educators can integrate into the curriculum. As Giddens (2000) points out, real transformation goes beyond rational thought, it involves genuinely sharing and understanding the emotions of others. Thus, empathic education fosters compassion and understanding towards non-human beings. Art educators can utilise various pedagogical approaches; by engaging the students directly with local contexts, such as the food industry, and produce works that depict the daily lives and conditions of farmed animals. Inspired by real-world observations and research, this method advocated by Kallio-Tavin (2020) allows students to gain deeper insights into the lives of non-human animals and develop empathy by understanding their perspectives.

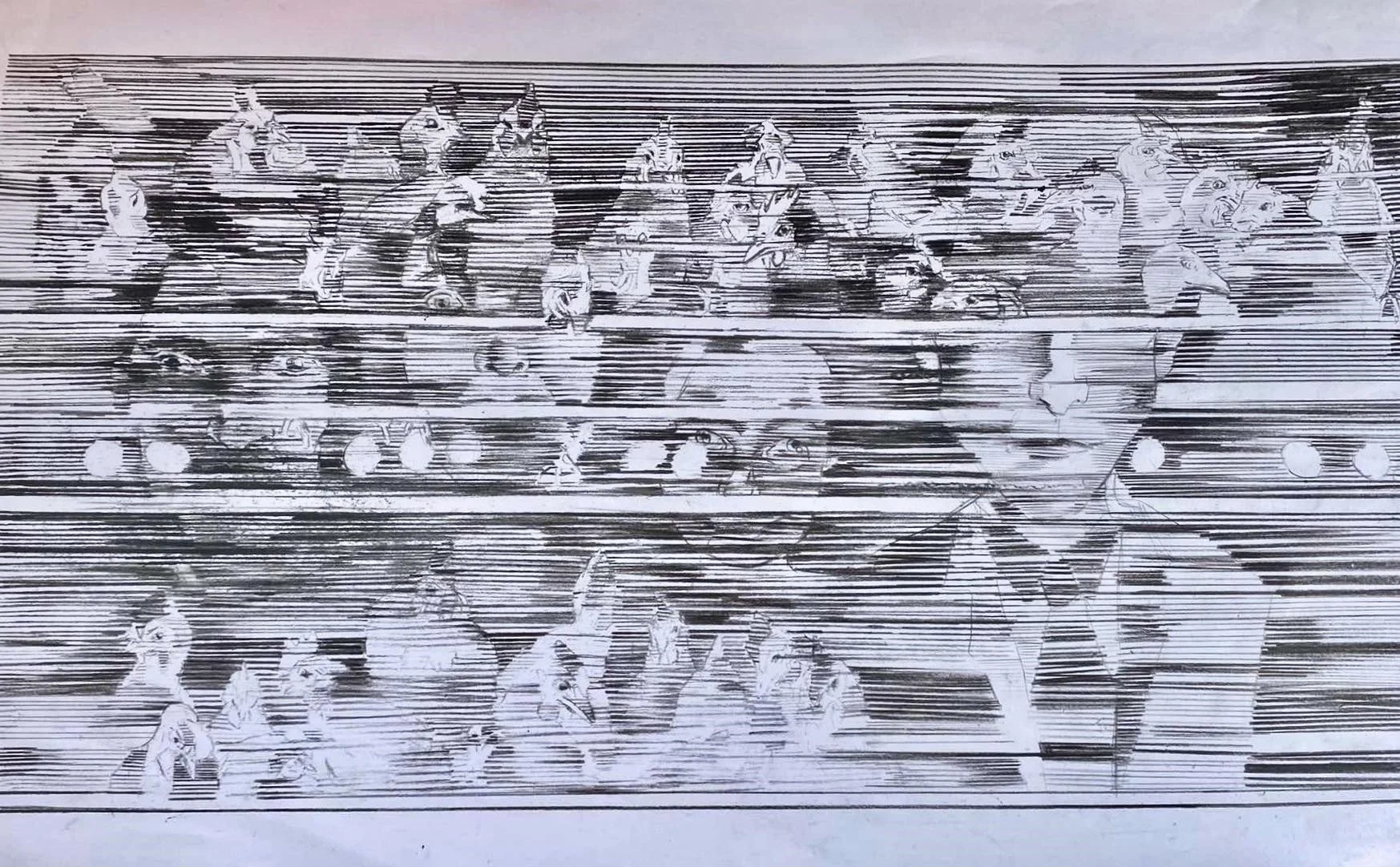

Beatrice Portelli, The Broken Herd, Graphite pencils on paper, 21cm x 29.7 cm, 2024

Philosophical discussions are another vital component of empathic education. Educators can be informed by ethical theories such as Singer’s Utilitarianism which emphasises reducing animal suffering and promoting equality (Singer, 1975). Regan’s philosophy, which challenges students to reflect on their roles in perpetuating or challenging societal norms, can also be included to provoke critical thinking and self-awareness (Regan, 2004). Through these discussions, students can question dominant narratives and hierarchies that place humans above non-human animals.

Additionally, I suggest using contemporary artists who address themes like anthropocentrism, sustainability and interconnectedness. By exploring the evolution of human and non-human relationships in art, educators can help students critically examine the power dynamics and ideologies that influence these interactions. Biesta (2017) argues that art education should foster dialogue with the world rather than focusing solely on self-expression. Thus, encouraging discussions around complex artworks can stimulate discussions about ethical issues and societal issues, ultimately guiding students to challenge established norms that shape our understanding of the world.

Art education, with its connection with ESD therefore is a powerful tool for addressing global issues. It links creative expression to real-world issues, encouraging reflection to move beyond our anthropocentric biases and truly value all life forms. Although breaking free from these concerns is challenging, art education provides diverse perspectives that challenge traditional thinking, helping us to look beyond our anthropocentric biases.

List of References

Achor, A. B. (1996). Animal rights: A beginner's guide: A handbook of issues, organisations, actions, and resources (Rev. ed.). WriteWare.

Biesta, G. (2017). Letting Art Teach: Art education “after” Joseph Beuys. ArtEZ Press.

Berger, J. (2009). Why look at animals? In J. Berger (Ed.), About Looking (pp. 3-28). Bloomsbury.

Kallio-Tavin, M. (2020). Art education beyond anthropocentrism: The question of nonhuman animals in contemporary art and its education. Studies in Art Education, 61(4), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2020.1820832

Kaspersen, L. B., & Sampson, S. (2000). Anthony Giddens: An introduction to a social theorist. Blackwell.

Regan, T. (2004) The Case for Animal Rights. University of California Press.

Singer, P. (1975). Animal Liberation: The Definitive Classic of the Animal Movement. HarperCollins Publishers.

Vella, R., & Pavlou, V. (2023). Art, Sustainability and Learning Communities: Call to Action. Intellect Books. Retrieved from https://www.intellectbooks.com/art-sustainability-and-learning-communities